In Nancy Meyers’s Something’s Gotta Give, Diane Keaton, after having her turtlenecks and then her heart ripped apart by Jack Nicholson, begins to weep and then to type. Diane plays an uptight playwright named Erica Barry and in the aftermath of her dumping, she’s cracked open—the words of her latest project pour right out of her. The seasons change and Erica continues to write and wail, wail and write, mouth open in comical anguish.

I love this scene because, well, I love a little feminine hysteria and Diane Keaton does it so well, and like most things Nancy Meyers, it’s an aspirational fantasy. I will never own a beach house in the Hamptons, I will never wear an all-white ensemble without soiling it, and I have never achieved divine emotional catharsis through writing. Allegedly, “everything is copy,” but artistic productivity has never been what flowed from my personal crises. Not to be melodramatic, but why would I want to layer one agony on top of another?

Writing is just what I do when a) conditions are ideal and b) I’ve exhausted all the other possibilities. Today, I was supposed to write this cute little essay, just for myself, just to clear the pipes. Reader, I’ve gone for a jog, made lunch, showered, cleaned the kitchen, attended to the urgent matter of opening my mail, watched an episode of Top Chef for a “break,” and it is now 4:45 p.m. I do a lot better with editors and deadlines, but I’m at a career juncture where I’m hunting both and forced to steer my own rickety ship.

Nancy and Diane aside, when I see someone onscreen go into a fugue state and pop out their play/screenplay/novel in the span of a scene, I’m outraged. Where is the endless revising, the beating of the head against the wall, the self-recriminations, all the stupid little walks you have to take to clear your head, the firm conviction in the middle of every project that wow, you must be very dumb and this is actually quite bad? The novelist Philip Roth once said, not at all melodramatically, “Coal mining is hard work. This is a nightmare.” (H/T: Mason Currey’s excellent newsletter about artists’ daily rituals).

If it’s so much self-laceration, so much torture, why do so many people do it or at least aspire to it? I guess because of the possibly deluded belief that you have Something to Say, because of a rush you may have gotten from seeing something published under your name, maybe because someone once said that they connected with something that you wrote, or maybe because you’re coasting high off the memory of having written a really good sentence.

Even depictions that are wise in other ways tend to romanticize the period when the work actually happens. Greta Gerwig’s adaptation of Little Women is sublime about the loneliness of having writerly aspirations, especially in adulthood, when the meandering days and unfettered creativity of girlhood give way to practical concerns, like trying to earn a living.

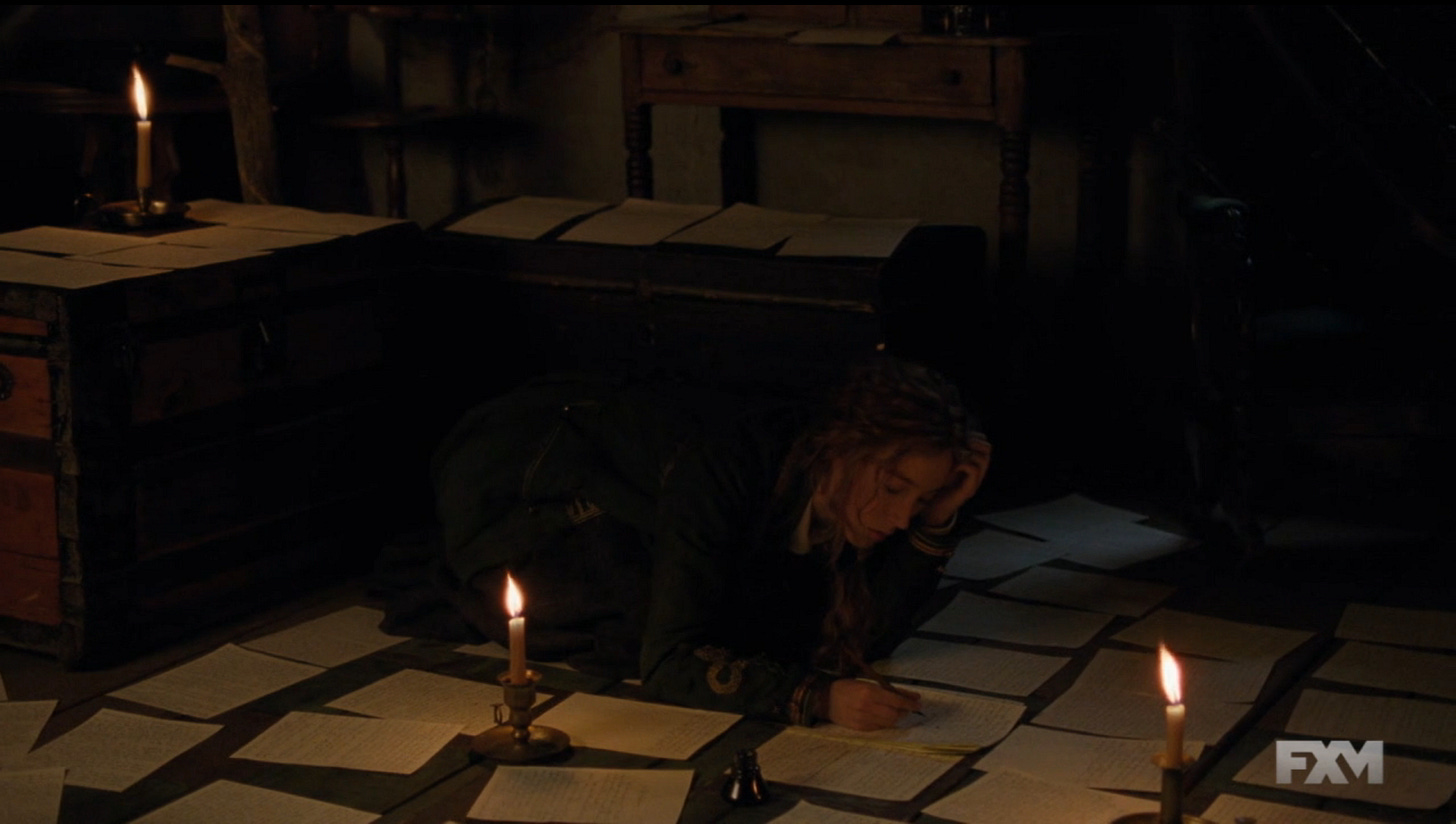

But Jo too experiences that mythical creative starburst. After Beth’s death and after Laurie marries Amy, a grieving Jo writes Little Women in a daze of sleepless nights, her pages laid out on the floor by candlelight, her hands cramping and smudged with ink. Isn’t that the hope? That you can create something timeless from your suffering?

But the slog, absent the soaring score, that satisfying crescendo, is more like the inner monologue that runs through Adaptation, a meta-comedy about the nervous breakdown the real screenwriter Charlie Kaufman had in attempting to adapt Susan Orleans’ book, The Orchid Thief.

“To begin... To begin... How to start? I'm hungry,” the fictional Charlie Kaufmann (played by Nicholas Cage) says to himself. “I should get coffee. Coffee would help me think. Maybe I should write something first, then reward myself with coffee. Coffee and a muffin. Okay, so I need to establish the themes. Maybe a banana-nut. That's a good muffin.”

Ah, there it is. The distractions, the cluttered brain, the perverse rewards system. Charlie’s monologue can get even darker, unleashing his most hateful thoughts about himself. “Do I have an original thought in my head? My bald head,” he asks himself. “Maybe if I were happier, my hair wouldn't be falling out.”

Possibly the reason TV and film sidestep the actual, ugly process of making art is because watching someone do it i.e. endlessly marinate in their own neuroses is uncomfortable and not all that compelling to watch.

I’ve wrestled with all kinds of fears and insecurities my entire writing life. I’ve tried to outrun them or shove them down but that’s mostly meant avoiding doing the thing that, for whatever reason, appears to bring me some satisfaction and fulfillment. I’m reaching toward the realization that maybe the fear is not something to conquer, but something that sits in the room with you every single day, alongside the scraps of paper and the half-eaten muffins, until it feels more like a companion than a ghoul.

And what if your worst fears come true? In the musical Tick Tick…Boom, based on the real life of the composer and playwright best known for Rent, Jonathan Larson is filled with visions of grandeur (“I’m the future of musical theater,” he says, only half-joking). He’s also a self-absorbed if charming menace and a reckless procrastinator who blows off his friends and loved ones to stay up all night and stare at a blank screen. His friends assure him that “there is only one Jonathan Larson”—that his talent is singular—but he doesn’t know that yet.

After eight years of toiling away at his first musical, Superbia, while waiting tables, absolutely nothing happens. No accolades, no money, no producers knocking down his door. “What do I do now?” Jonathan asks his agent (Judith Light), defeated. “You start writing the next one,” she says. “And after you finish that one, you start the next. And on and on. That’s what it is to be a writer, honey.” Jonathan Larson survives this rejection, he does write the next one, but passes away from a heart condition the night before Rent is set to debut off-Broadway.

It turns out that there are things even crueler than failure, than having to stare down a blank page. Life is short and fickle, so it has to be on to the next one.

Small recommendations:

Heather Harvilesky’s writing diary is the only one I’ve ever believed

I also love Sarah Miller’s Popula essay, The Movie Assassin

Each week that passed I wrote something amazing and nothing happened, so I dug in and wrote harder. I thought I was trying to get somewhere. I thought there was somewhere to get. I had no idea that what I was experiencing was being a writer, and that no matter what happened, good or bad, I would feel exactly the same way forever.